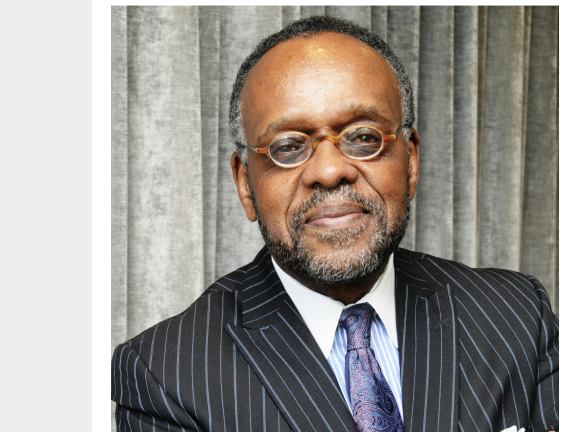

A Global Conversation with Oliver Saint Clair Franklin

As the 2023 Lifetime Achievement Globy Awardee and British Honorary Consul of Philadelphia, Oliver Saint Clair Franklin’s story explores the experiences and insights of a career that has spanned continents and decades. Franklin’s interests and talents range from academia, arts, culture, and international business. His narrative begins with a significant chapter in the United Kingdom, where postgraduate studies at the University of Edinburgh led to a transformative experience at Oxford's Balliol College. The UK became not just a location but a hub of cultural enrichment during a crucial phase of his life. Following his studies, he was led to Philadelphia with the promise of love, revealing itself amid a city facing socio-political challenges as a place of historical resonance and unexpected warmth.

Immersing himself in the cultural fabric of the city, Franklin initiated a National Black Film Festival, contributed to the Pennsylvania Humanities Council, and engaged with the National Endowment for the Arts. As a linchpin for the city’s cultural community, Franklin served with the Goode administration, where was the Deputy City Representative for Arts and Culture and Chief of Protocol. Through innovative programs and a commitment to community engagement, he left an indelible mark on the city's cultural landscape. The thread of cultural promotion is woven into his subsequent endeavors, including pioneering programs that fostered cultural exchange between students in London and mid-career minorities in UK investment banks.

Franklin’s interests aren’t limited to the arts. In the realm of global finance, Franklin ventured into post-apartheid South Africa, spearheading one of the first US registered mutual funds to invest in the country. The decision unfurled against the backdrop of historical shifts and the complexities of economic transitions, offering a nuanced perspective on the interplay between investment, trust-building, and social change. As a British Honorary Consul, he has continued to bridge the gap between the United Kingdom and the United States. Franklin reflects upon distinguished honors, a lifetime of service, and a gaze into the future—a future that holds intriguing projects and a continued commitment to global engagement. Through this expansive conversation, we are invited to traverse a life woven with threads of cultural appreciation, economic acumen, and a steadfast dedication to service.

You started in Baltimore and then arrived in Philadelphia in the 70s, starting what would blossom to become a remarkable career that has taken you all over the globe. Can you talk a little bit about how your relationship with the United Kingdom came about, and why you first decided to move to Philadelphia?

My relationship started as a post-graduate. I went first to the University of Edinburgh and spent a year there and was encouraged to apply to Oxford or Cambridge. I applied to Oxford on my own and I was lucky enough to gain admission. I spent two years at Balliol College at Oxford and being a postgraduate was the perfect time to absorb another culture because I didn’t have any encumbrances. No mortgage or a family yet, and I had the opportunity to be with students. If you want to learn another culture when you’re young, the best way is through meeting other students.

I came to Philadelphia following my girlfriend, who has since become my wife. She’s from Baltimore also and was here studying here for a master’s and then decided to pursue a Ph.D. I was lovesick as one can be at that age. So I left my position in Baltimore and came to Philadelphia to be with her. We both decided we would give Philadelphia a try and it worked out much better than any of us had anticipated.

Would it be safe to say you had a good first impression of Philadelphia? Was it a city you saw yourself staying in?

Yes, first of all, I had a good surname --Franklin. There’s so much mention of Ben Franklin that I just began to absorb the feeling of being a ‘Franklin.’ One Franklin sailed down from Boston and became world famous, and the other Franklin crawled up from Baltimore and stayed.

Frank Rizzo was mayor then and to be honest, it was a very tough time in Philadelphia. He was a blue-collar commissioner of police when the black liberation movements were ramping up in the city and he used police power to try and crush those movements. That catapulted him to becoming mayor. It was indeed an extremely tense period. The city doesn’t look at all like it does today. It had a grimy feel to it, a lot of graffiti everywhere. Yet beneath all of that contemporary tension, there was that historical feeling that seemed to surpass the moment that we were in. It became a really welcoming city in the historical aspects, whether it was going to Independence Hall, seeing city hall, or the parkway.

During your early time in Philadelphia, you founded a National Black Film Festival, were the treasurer of the Pennsylvania Humanities Council and were involved with the National Endowment for the Arts, and spent time serving for the Goode administration as the Deputy City Representative for Arts and Culture and Chief of Protocol. Why is the promotion of art and culture integral to the fabric of a World Heritage City?

When I came to Philadelphia few knew what a B.Phil degree was. As I was beginning to go around and seeking opportunities, someone suggested I meet Martin Myerson, the president of the University of Pennsylvania. I got an appointment. President Meyerson was the ultimate networker and knew one of my British tutors. It was my first big break.

I started as an assistant to him, which was a way to learn about the university on an operational level. But many younger faculty were moving into West Philadelphia, a working-class Afro-American community and the university wanted to get involved, so I suggested that I would love to be involved in that effort.

I became the Deputy Director of the Department of External Affairs, which allowed me to keep one foot in academia with the Urban Studies department and one foot in the community. That was so exciting. It was also the beginning of the black movie era, when Hollywood discovered the back audience. These films were very controversial in the community, and everyone had an opinion. Penn had a state-of-the-art theater, and I suggested a historical black film festival to bring the ‘community’ on to the campus. We found funding and screened films on Sunday afternoons during the summer. There were 950 seats in the theater and by the second Sunday the Annenberg Center was filled. We gave the audience what they wanted - a historical understanding with discussions after those screenings with experts, mainly faculty at Penn. That’s how my relationship with the PA Humanities Council and the National Endowment for the Arts was created. We kept building, starting in West Philly, and then in five places around the city, then five cities in Pennsylvania, then five big cities across the country. It began to grow, and we began to focus on young black filmmakers, like Spike Lee and other directors that are now household names.

W. Wilson Goode, who would go on to become mayor, came with his wife to the film screenings. That’s how I became the Deputy City Representative for Arts and Culture and Chief of Protocol. When he began his campaign for mayor, he asked me to organize the cultural community. That seemed like a great opportunity to get involved in policy and in understanding how politics works in Philadelphia. When Goode won, he implemented a thirteen-point program we created by listening to the cultural community during the campaign. We increased funding, had programs for housing and artist studios, had the Anti-Graffiti network, which became the Mural Arts program and created the film office. As a result, the mayor became a very successful arts and culture mayor.

Whenever you started that position, what sorts of experiences did you have in the community already that you felt were really important to center and bring into your work with the city?

Before he became Mayor, Wilson Goode was deeply involved in community development. And he gave me a master class on working in the community. He told me to be patient and listen and over time you’ll build trust. I am also the son of a minister and I learned early on that everyone is important. My father taught me that people may not remember what you said, but they’ll always remember how you made them feel. So, I took my family experience and the lesson from the Mayor into the work. Artists are very articulate, and I listened to them. Over time people began to feel that the city, at least on the cultural side, had their ear. Once you develop trust, implementing programs that benefit the community and the entire city is a lot easier.

Yes, the World Heritage City designation is the most important designation we have received this century. We have a renaissance going on here at the moment, and there’s a lot of momentum. The World Heritage City designation is a part of that momentum. Arts and culture are integral because when people come to Philadelphia, they come to visit the arts and cultural components of the city. Winston Churchill doubled the arts budget during the war and parliament asked why. Because, he said, “I want people to know what they’re fighting for’. So, culture is an intricate part of who we are.

You have led and been involved in programs that facilitate student visits to London and create opportunities for mid-career American minorities in UK investment banks. Could you share more details about these initiatives, and how have they promoted cultural exchange and increased diversity in the field of finance?

Joe Jacovini, a prominent attorney here helped me move into investment management after my stint with the city. Finance is a global system. If a person is with an established investment firm, seven times out of ten, a lot of their business is going to be done internationally. And, in order to build a well-rounded career, it’s really important for early-career people to get a global experience as soon as they can.

Our program was called the City Fellows Scheme. It’s called city fellows because the business district in London is called ‘the city’. It was a project where I could bring my web of relationships on both sides of the Atlantic in service to the early career development for American minorities. The challenge was convincing British firms on the value of having these professionals on their teams. And, on our side, convincing young professionals to leave their firms for a minimum of two years in the UK. But by year three of the program, many UK firms were asking to participate and our applications surged.

We tried to match the selected candidates with the selected investment houses in London and Edinburgh. We made sure that every person that went to UK had a career path. These were not internships - they were jobs. They were jobs that UK people competed for. And, one had the option of staying on. There are ten fellows still in London and doing very well with major careers at Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, NatWest and others. One has a major executive position with an Austrian bank. Everyone who went through the program, even those who decided to return to the US, came back a different person. They often returned to better U.S. positions because of their global experience.

Most important, this was a self-funded program. No foundations, or investors. Just prorating everyone who participated in the management cost. And when the program has run its natural course after ten years, we decided as a group to close it. Self-reliance is important.

Young people should not underestimate how global everything is. Every opportunity for international experience that you can take advantage of, particularly if it’s your focus area, you should jump at it.

To talk about jumping at opportunities and international relationships, I wanted to ask another question related to your relationship with South Africa. You were the co-managing partner of the first US registered mutual fund to invest in South Africa in 1996. What was that experience like for you to be amongst the first to invest in post-Apartheid South Africa?

It began when Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk received the Liberty Medal in 1993. I had an opportunity to meet Nelson Mandela, and to have a serious conversation with him. At that time, I was a senior vice president at Fidelity investments in Boston. Fidelity was and still is one of the largest investment firms in the world, but they weren’t invested in Africa at that time, so I suggested to the chairman that we should have an African fund for our institutional clients. My area was institutional investing, and our clients were pension funds and were large family offices. Our team spent a few months researching Africa and it was still too early for Fidelity, but they saw it as an opportunity for me to develop my own firm for this effort with their backing. So, I found a partner, and with the backing of Fidelity went into South Africa.

It was not easy because we were there before the first all-race election and at that time, white South Africans for the most part were convinced that black South Africans would take retribution after years of abuse during apartheid. But the black businesspeople in South Africa assured me that wouldn’t happen because they wanted to run a country. The last thing they wanted to do was burn down the factories that provided an opportunity to provide employment for the people. We were convinced it wasn’t going to happen.

Many white South Africans began emigrating out of South Africa to Britain and America because of this fear, and in the process of emigrating, they were selling their assets at deep discounts. I call it the ‘fear discount’ which provided a lot of opportunities for firms to come in and acquire these discounted assets, which became in time a very good investment. The challenge was convincing Americans to invest in South Africa. I spent two weeks in Cape Town and two weeks in the United States raising assets. And it was very challenging but once we acquired assets and began to manage them it was a different story. The strategy was always to stay in three years, raise assets, and seek out a larger American or British firm to acquire us.

And that strategy worked out very well. We were very focused as businesspeople that we would never be big enough to service a large country like South Africa. Our goal was to demonstrate South Africa was a good investment. To that extent, it was a huge success, and it was certainly one of the greatest experiences of my life to have lived in South Africa during that period.

Can you elaborate on your role in enhancing bilateral relations between the UK and the United States, and how these efforts have been meaningful for both nations? What does that look like at a city level?

The British trade and investment strategy is state by state with MOU signings around various sectors. Kemi Badenock, the Secretary of State for Business and Trade was in Florida three weeks ago concluding a signing there. And we’re working hard to conclude a signing in Pennsylvania as well. I work closely with the British American Business Council here in hosting business delegations and sponsoring Philadelphia delegations. I coordinate with the New York British Consulate and the embassy to bring in high-level government and private sector executives to visit Philadelphia and meet politicians and business leaders. We also build around opportunity events like the upcoming Phillies game next season in London. And our sector focuses are fintech, biotech, life and health sciences, agriculture, clean energy and procurement. And let’s not forget how important Royal visits are because of the global press that follows them. The number of British tourists increased significantly after the visit of Prince Charles in ’07. The same with Prince Edward, the duke of Edinburgh. And finally, the UK is the largest country that students here visit for a semester abroad and post graduate work. So, our efforts are focused, meaningful and sustainable.

As a leading member of the business community of Philadelphia, how do you feel the city has evolved economically over the years? Where have improvements been made, and where are they still needed?

Yeah, we have evolved tremendously over the years. When I first returned from aboard here, the international terminal was separated from the airport and looked like an army barracks. Now the airport is a very welcoming place where people say welcome or welcome back. The most important thing that’s changed is the attitude. That has changed because we are a World Heritage City, we’ve got the World Cup, and 2026 coming in, so everyone is focused. What is still needed is to get business in more partnerships with the city and with communities. Business is a very dynamic force. My friend Ed Satell founded the Satell Institute, a forum for Company CEOs to focus on corporate social responsibility. There’re no fees to join but each CEO must make a commitment to support a non-profit of the company’s choice for a minimum of $25K each year for four years. Those meetings are amazing. Everyone is focused on business’ role in corporate social responsibility. Imagine the impact of the Satell Institute. We need more innovative business leaders to create programs of engagement like this.

Your significant recognition as an Officer of the British Empire in 2002 and later as a Commander of the British Empire in 2022 highlights your exceptional service. Can you talk a little bit about what these distinctions mean to you?

Well, the British have a unique form of recognizing ordinary people through the honors system sanctioned by the monarch. There are various levels. The MBE is “Member of the British Empire,” recognizes extraordinary work in your local community. The OBE is “Officer of the British Empire” which recognizes work on a broader level. When you become a CBE, “Commander of the British Empire,” its recognition of an even broader scale. Becoming an OBE and then a CBE ten years later is a recognition from the British that I’m doing my job that I’m growing in the role.

When you think about it, it means an awful lot internally. These honors represent a high degree of giving back, and that’s what I’m most proud of. Most Brits and members of the Commonwealth receive Royal investitures because members of Royal family present their insignia to them in a formal ceremony in one of the palaces. All these honors are personally signed by the monarch. And I've often wondered how many hours the present and late monarch spent reviewing and signing appointments. When Prince Edward presided over my CBE investiture at the British embassy it was a ‘royal investiture,’ making me one of the few non-Commonwealth Brits who has had a royal investiture.

As the recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Globy Award, there are many past accomplishments and distinctions that have shaped your career. Looking forward, do you have any projects or plans coming up?

This Lifetime Achievement Award has given me permission to reflect and, hopefully, slow down. But I'm fascinated with Philadelphia's central role in the upcoming Semiquincentennial in 2026.

Aside from my business interests, I’m very interested in media projects. I made a film with my Oxford college two years ago on Oxford and the transatlantic slave trade. That included not just the film but a two-year teacher’s program with the Museum of the American Revolution for teachers in the UK and Philadelphia. It was important and impactful, and I learned a lot.

I’m now producing a project about our Founding Era on Haiti, the second republic in the New World and the US. It’s a history very few Americans know about and it’s an important period for how these two nations, one governed by self-emancipated Africans and the other governed by many slaver owners negotiated a way to work together to defend themselves against the European powers in the Atlantic Ocean. It’s a story about race, a pandemic, immigration, shared national interest, the formation of political parties and the evolving definition of what it meant to be an American. It’s a fascinating story because most of the buildings from the era are still here. And I’m hopeful it will contribute to our national conversation during the Semiquincentennial.

If you could offer one piece of advice for Philadelphians who want to get involved in global affairs in the city, what would it be?

It’s very simple. Show up! Attend the World Affairs Council and the Global Philadelphia programs. Then you’ll be in a network. Find mentors who can advise you and plan your level of engagement. If you’re a student, take advantage of opportunities at your educational institution.

Most important, learn from your mistakes. Failure is a part of life. And in this country, it’s not how you fall, but how you get up that counts.