Chinatown's Legacy of Resistance, Resilience, and Renewal

In 1966, a small group of Philadelphia’s Chinatown residents united under one goal: stop the Vine Street Expressway from destroying the Holy Redeemer Church and School, the spiritual and educational core of their community. They succeeded, and in doing so, planted the seeds for what would become the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation (PCDC), a community anchor that has helped shape not just a neighborhood, but a political and cultural identity.

Nearly 60 years later, Chinatown remains a rare example of an urban village — dense, deeply rooted, and fiercely self-defining — even as outside pressures continue to mount.

“Chinatown was sitting in a blighted neighborhood that was identified for urban renewal by the federal government,” says John Chin, executive director of PCDC, who has been with the organization for over 25 years.

“So the housing was an outcome of solutions to address the problem, which is how do we preserve and ultimately protect Chinatown.”

More than just a cultural enclave, the neighborhood is a living story of resistance — shaped not only by its institutions, but by the generations of families, business owners, and activists who have fought to keep it whole. Established in 1871, it began with a single laundry opened by Lee Fong, a Cantonese immigrant fleeing the hostile, anti-Chinese western plains of the United States to start over in the east. Over the decades, it has grown into a diverse, multilingual, intergenerational neighborhood that pulses with flavor, memory, and defiance.

By the early 20th century, despite restrictive immigration laws and racial hostility, Chinese immigrants laid deep roots — forming mutual aid societies, opening family-run businesses, and building spaces for worship and celebration. Immigration reforms in the 1960s opened the gates to new waves of Chinese, Vietnamese, and later Korean and Southeast Asian residents, who added linguistic and cultural layers to the already diverse neighborhood.

Walking through the ornate Friendship Gate today — a gift offered by Philadelphia’s sister city Tianjin in 1982— you leave the glass towers of Center City behind and enter a tightly woven world. There’s crispy roasted duck in Ting Wong’s window, families strolling past herbal pharmacies, teens sipping boba on folding stools, and elders clustered outside apartment stoops on hot summer evenings. Cantonese, Mandarin, Vietnamese, and English mingle freely in the air.

What makes Chinatown unique is not just its atmosphere, but its continuity. “Even though we're 5,000 residents now, a lot of people still know one another. It’s still a small community,” said Chin, who also grew up in the neighborhood. “I love it when I see people sitting out on their stoops just talking in the evening.”

Chinatown also serves as a cultural magnet for Asian international students attending universities across the region. Institutions like Penn, Temple, and Drexel have student bodies that are between 10 and 20 percent Asian. Before recent shifts in immigration policy began to slow that influx, these students contributed to a vibrant presence in the neighborhood. On the storefront lined streets, they find familiar tastes, languages, and rhythms that offer a sense of belonging far from home.

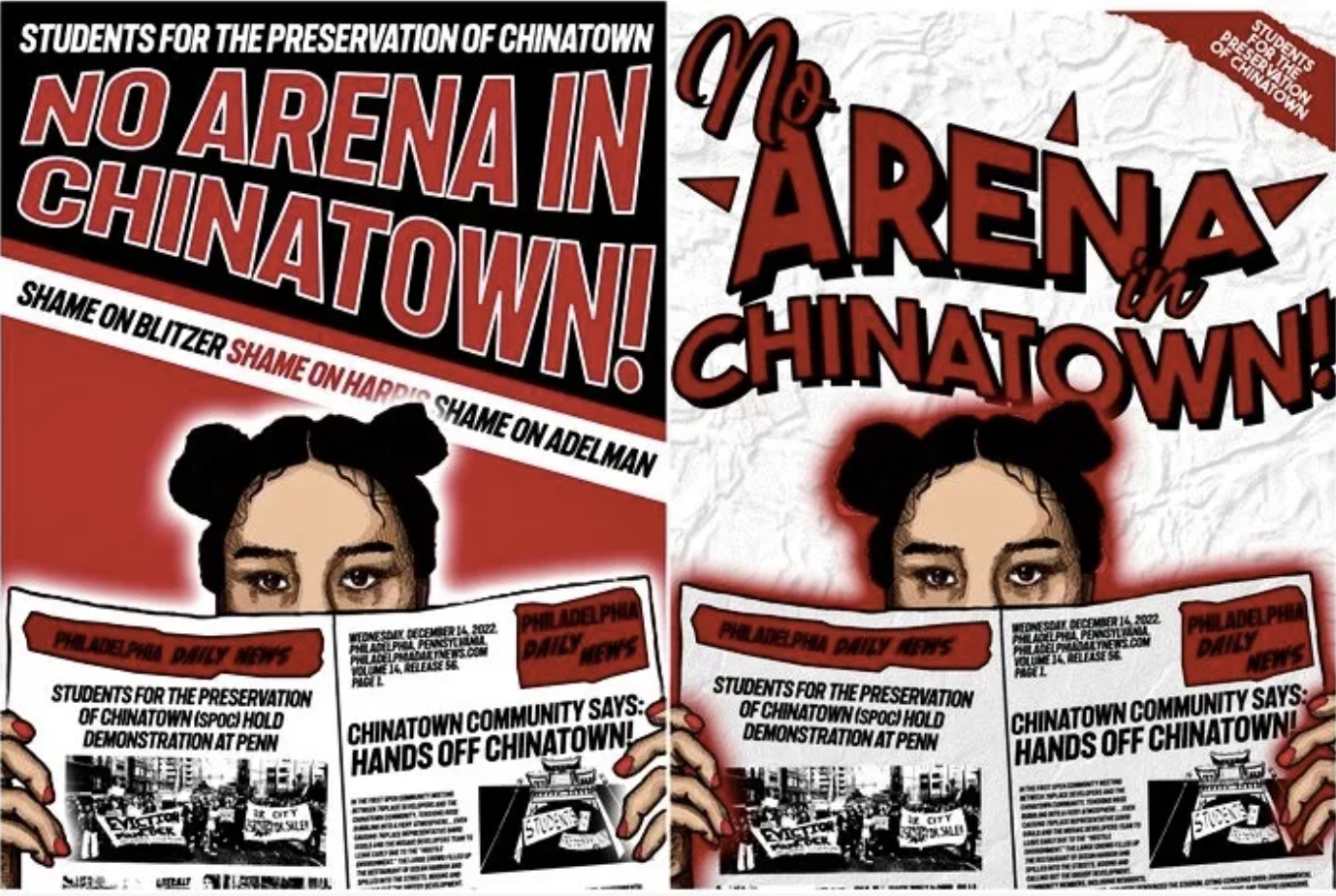

But that continuity has never been a given. Over the last century, Chinatown has fought back against highways, prisons, stadiums, discriminatory immigration policies, and corporate development. Most recently, the proposed 76ers arena reignited fears of displacement. The $1.3 billion project would have brought massive foot traffic, rising rents, and potential cultural erasure to a neighborhood already under pressure.

Flyers resisting these efforts papered shop windows. Community-led teach-ins, multilingual town halls, and citywide coalitions pushed back hard.

Ultimately, the proposal was scrapped, constituting a victory not just for property lines, but for cultural survival. “When the time is needed, our community does come together,” said Chin. “That’s what makes Chinatown so attractive. There’s solidarity, but it takes effort.”

That effort goes beyond protests. Chinatown thrives because of the ordinary but intentional ways people preserve identity — through celebration, food, language, and mentorship. Events like the annual Chinatown YèShì Night Market, the Chinese Lantern Festival, and the Chinatown Scavenger Hunt draw thousands and serve as both economic lifelines and cultural affirmations. Every winter, Lunar New Year parades fill the streets with fireworks, lion dancers, and marching bands for tourists and residents alike.

Local organizations — like the Asian Arts Initiative, Asian American Women’s Coalition, and a network of churches and small businesses — help anchor youth programs, ESL classes, and intergenerational storytelling. It’s not one group carrying the weight; it’s a constellation of community caretakers.

Even as Chinatown celebrates victories, challenges remain. Gentrification continues to ripple outward from Center City. Rising property values threaten to push out lower-income tenants and aging residents. And many business owners are still recovering from COVID-era losses.

“Some of the older businesses are still struggling to adjust,” said Chin. “They want to go back to the way things were.”

He points to a range of transitional challenges — most notably, the shift from Chinatown’s past as a late-night destination, with restaurants serving until 4 a.m., to a new reality shaped by changing consumer habits, like earlier dining hours and the rise of delivery platforms like Uber Eats.

The community’s future may depend on how it bridges those generational and economic gaps while keeping its values intact.

The PCDC has made it its mission to target these growing pains alongside other community issues with numerous initiatives, one of the most successful being the Main Street Program. This flagship program has supported a diverse lineup of over 400 local businesses in the neighborhood with one-on-one assistance to tackle difficult administrative procedures and roadblocks such as securing city-sponsored grants and funding, navigating obtaining proper permits, marketing and promotions, trash disposal, post-COVID revitalization, and more.

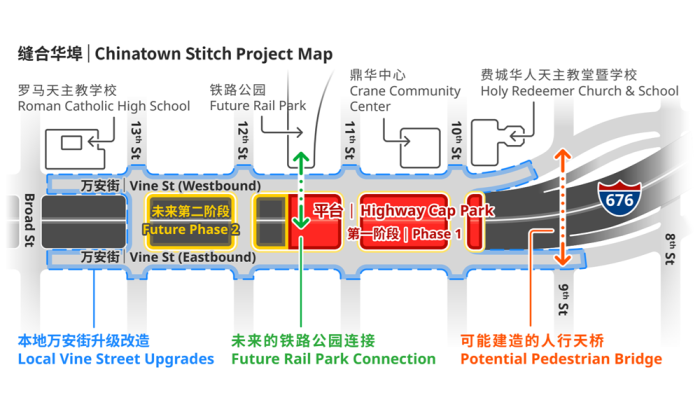

They have also taken on the role of guiding businesses to adjust their business model to encourage a steady stream of both local and visitor traffic. Nearly 60 years after residents first united to stop the Vine Street Expressway from tearing through Holy Redeemer, that same spirit drives the Chinatown Stitch Project. Launched in 2023 by the city and facilitated by the PCDC, the project aims to heal the damage caused by that very highway — reconnecting a divided neighborhood with green space, safer streets, accessible design, and public-use buildings.

A planned 1.5-block highway cap between 10th and 12th Streets will help restore walkability and community connection, while job training programs will ensure residents share in the economic benefits.

Looking ahead to the 2026 Semiquincentennial, the PCDC also hopes to renovate and revitalize the Friendship Gate — a symbolic restoration of Chinatown’s iconic entrance — pending city support and funding.

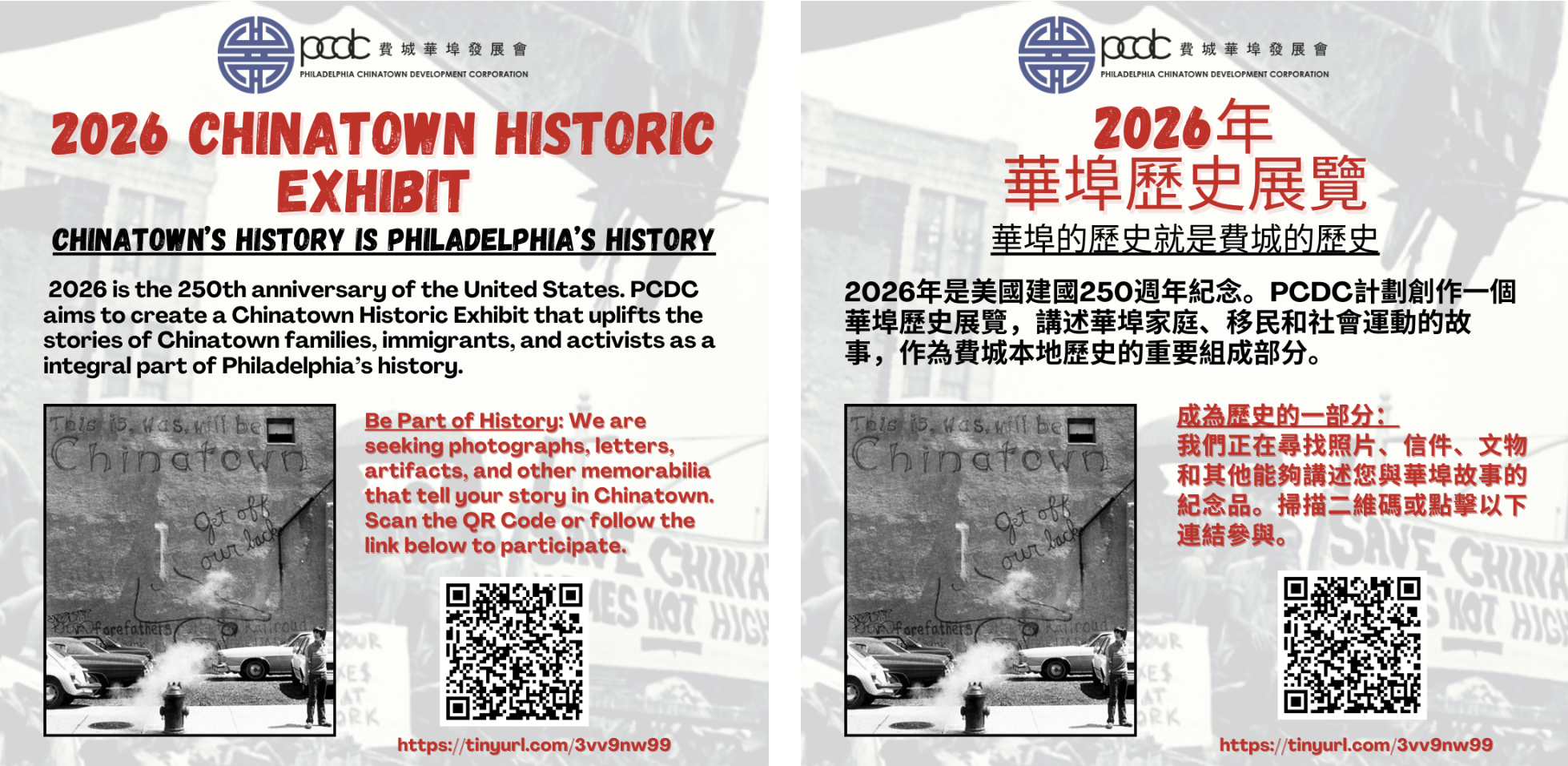

Alongside this transformative initiative, the PCDC has put together the Chinatown History Exhibit Project. Going on display in April 2026, this project is "a temporary exhibit to celebrate the history of Philadelphia’s Chinatown, illuminate the 150-year Chinese immigrant experience, and sharing the wider stories of Asian Americans today."

Chinatown’s story is ultimately not one of nostalgia, but of presence. A place where children grow up knowing their neighbors, where immigrants still find a first foothold, and where and where language and culture remain woven into daily life.

And for all its battles, Philadelphia’s Chinatown stands strong — not just because of what it resists, but because of what it continues to build.