Contact Information

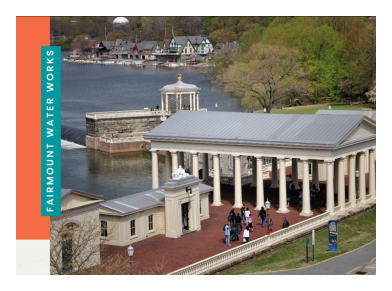

Fairmount Water Works

640 Waterworks Dr

Philadelphia, PA 19130

United States

Fairmount Water Works

Fairmount Water Works

While serving as the capital of the young nation in the 1790s, Philadelphia was swept four times by yellow fever. The first and worst epidemic, in the summer of 1793, killed an estimated 5000, ten percent of the population, and caused 20,000 to flee into the countryside. In response, in 1798 the city created the Joint Committee on Bringing Water to the City—usually called simply the “Watering Committee.” Although it would later be determined that yellow fever was transmitted by mosquitoes, at that time, suspicion fell on the city’s water supply, which came from wells that were known to be tainted by seepage from adjacent privies.

To address this problem, the Watering Committee determined to pump water from the Schuylkill River and distribute it throughout the city by means of a comprehensive network of pipes. Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764-1820), America’s greatest architect, was hired to build a revolutionary steam-powered system. This comprised an intake pumphouse on the river and a distribution pumphouse on Center Square, where the water, lifted by steam to a tank, would fall by gravity into miles of hollow-log pipes. The system—the first of its kind in any substantial city—went into operation in 1801.

The central reservoir proved to be too small, and in 1811 the Watering Committee commissioned Frederick Graff (1775-1847), Latrobe's chief assistant on the Center Square project, to implement a revised plan. Fairmount, a rocky hill that rose above the river at the northwest corner of the city, was identified as the site for a larger, naturally elevated reservoir. At its foot, Graff built a chaste, house-like building to contain the steam engine and pump needed to raise water to a basin carved into the hilltop, 90 feet above. That building is preserved today.

The new pumphouse was put into operation in 1815. It was capable of moving two million gallons every 24 hours, and the reservoir held 22 million gallons—enough to meet the city’s needs. But firewood was costly, and the steam engines exploded disastrously in 1818 and 1821, and so Graff undertook to devise a cheaper and safer system in which steam was replaced by water power. Built in 1819-1822, his design included a 1,600-foot-long dam across the Schuylkill (said to be the longest in world), which created a six-mile-long lake. As the lake’s waters tried to fall to their natural level, they were channeled through a new millhouse, sternly neoclassical in style, whose roof was at ground level and in which Graff installed eight water wheels to drive the pumps.

The new system was much cheaper and more reliable to operate, and the waterworks became profitable for the first time. It was also silent and smokeless, and the Watering Committee undertook to develop the picturesque site as a public garden. Walkways were laid out and flower beds installed. The roof deck of the millhouse was enlivened by two classical temples (the Watering Committee office and caretaker’s house) and its entrances were embellished in 1825 by two allegorical figures by the sculptor William Rush: “Schuylkill Chained” and “Schuylkill Freed.” Rush’s “Nymph and Bittern” was subsequently moved here from the abandoned Centre Square facility.

When Graff died in 1847, he was succeeded as chief engineer by his son, Frederick Graff, Jr. (1817-1890). He oversaw the building of a second millhouse, angled out into the river, and the installation in it and the original millhouse of six Jonval turbines, which were more efficient than the waterwheels. He also built the columned classical pavilion atop the first millhouse in 1868-1872, which does much to give the complex its belated Greek Revival appearance.

In order to limit water pollution caused by industry, the Watering Committee began to purchase properties along the river, starting with Lemon Hill in 1845. The younger Graff landscaped this new property, and this acquisition of riverfront lands laid the foundation for Fairmount Park, established in 1867.

Unfortunately, these measures did not prevent Schuylkill from becoming increasingly dirty, and the construction of new, filter-equipped water intakes on the Delaware and elsewhere on the Schuylkill made the Fairmount Waterworks obsolete. In 1909, all but one turbine were stopped, and, when it, too, was stilled in 1911, the buildings and the reservoir were transferred to the Fairmount Park Commission. The hilltop reservoir site was given to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for its new home, and the engine house and the millhouses were modified to accommodate the city aquarium and a swimming pool, which closed in 1962 and 1973 respectively. Restored in several campaigns, the buildings now house the Fairmount Water Works Interpretive Center and a restaurant.