Laurel Hill East

3822 Ridge Ave.

Philadelphia, PA 19132

United States

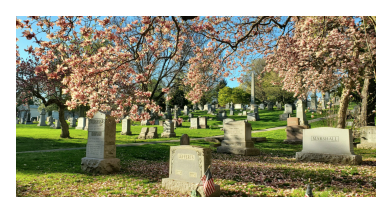

Laurel Hill Cemetery

Laurel Hill Cemetery

This 74-acre tract, whose hilly terrain rises as much as 120 feet above the Schuylkill River, is the nation’s second “rural cemetery,” an institution invented in the early nineteenth century to solve a pressing problem: the difficulty of providing respectful and hygienic burials in crowded and quickly growing industrial metropolises.

Laurel Hill, founded in 1836, exemplifies the creative solution to this problem: a cemetery without a singular religious affiliation, located well outside the city on a site chosen for its picturesque character. This invention both transformed the manner in which the dead were honored and provided a model for the public parks and gardens that would be created in coming decades.

The first rural cemetery was Mt. Auburn, located outside Boston and dedicated in 1831, and it was the model for the cemetery that John Jay Smith (1798-1881) began to plan for Philadelphia in 1835. An accomplished writer, newspaperman, and horticulturalist, who worked as a librarian at Library Company, Smith convened a group of similarly minded citizens, and in 1836 they formed a corporation and purchased the riverside estate of Joseph Sims, Laurel Hill. By 1861 they had added three adjacent properties.

The cemetery conducted a design competition, in which a newly arrived Scottish architect, John Notman (1810-1865) beat established Philadelphians, including Thomas U. Walter and William Strickland. Notman designed the Roman Doric gate house, with small houses for the porter and gardener, a Gothic chapel, and the superintendent’s cottage. These were built immediately. The chapel and cottage were demolished in the 1880s, but the rather severe gatehouse survives, although altered.

Also surviving is the pinnacled shelter that Notman created just inside the gate for the sculptural group “Old Mortality and Sir Walter Scott” (1836). The work of Scottish sculptor James Thom (1802-1850), whom the architect had recommended, it depicts the popular novelist in conversation with one of his characters, an elderly stone carver who traveled from place to place, re-chiseling the eroded inscriptions on grave makers.

Notman designed the curving walks and roads of the first part of the cemetery, near the gate, whose picturesque character was influenced by the design of Kensal Green Cemetery in London. Smith oversaw the planting, which would ultimately number 6,000 trees and shrubs representing 700 species. This work put Smith in frequent contact with the nation’s leading landscape gardener, Andrew Jackson Downing, whom he succeeded as editor of The Horticulturalist. To increase the cachet of the cemetery, Smith also arranged the reinterment of the remains of several famous figures from the Revolutionary War era.

This combination of picturesque beauty, botanical variety, historical significance, and, of course memories of the deceased made Laurel Hill a popular destination. Downing reported in The Horticulturalist that "nearly 30,000 persons…entered the gates between April and December 1848."

While Smith continued to head the Laurel Hill Cemetery and oversee its plantings, Notman’s activity ended soon after his buildings were built. The next section was laid out by civil engineer James C. Sidney (ca.1819-1881), and subsequent tracts were designed by others.

The 33,000 burials at Laurel Hill include many of the region’s most important leaders, most significant artists and designers, and wealthiest industrialists and financiers. Their mausolea and monuments were created by leading architects and sculptors in all the popular styles of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: Greek, Roman, Gothic, Egyptian, and Art Nouveau. An especially impressive group of tombs in the central part of the cemetery is called Millionaire's Row.