Postmortem Project Exhibition at the Mutter Museum

For the science and medicine enthusiasts out there, the Mutter Museum is a wonderfully grotesque place to visit, and it is not for the faint of heart. During my first visit years ago, I was an aspiring medic of some sorts, following in the footsteps of my Physician Assistant father, and found the museum incredibly interesting. I marveled at the wall of skulls and even giggled at the sign underneath one that simply read “idiot,” feeling a sense of humanity as I imagined my own future gravestone potentially bearing the same phrase.

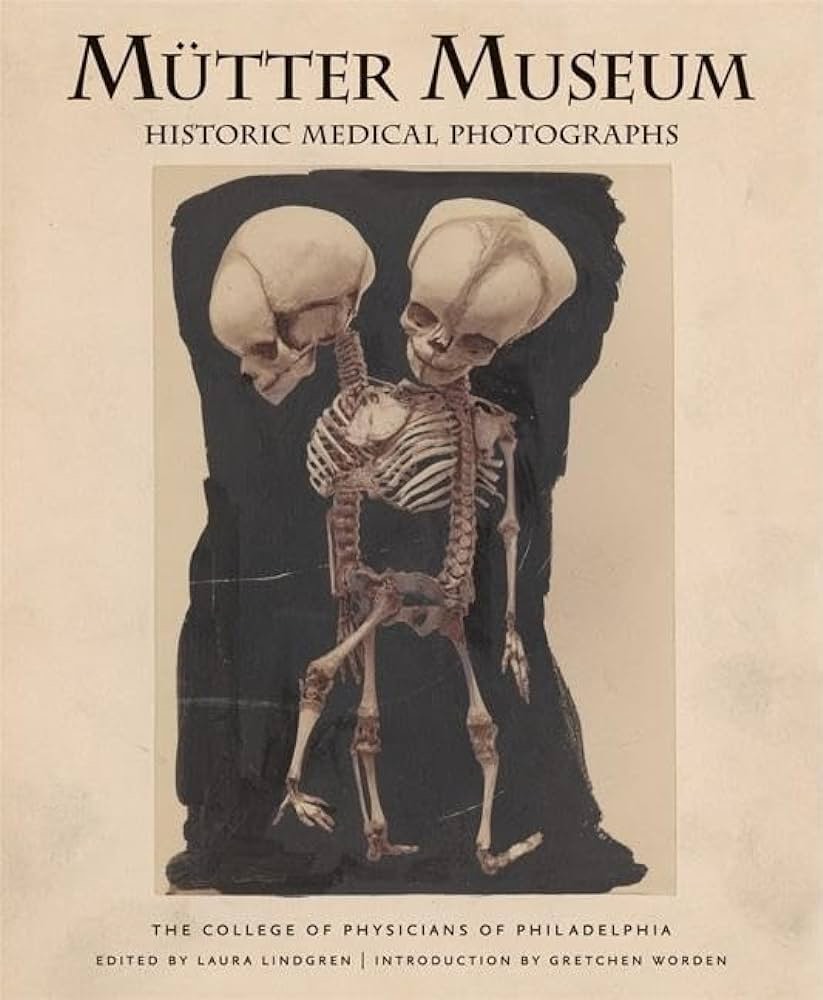

The Mutter Museum provides a whirlwind of specimens and bodily entrails that can make even the toughest person dizzy with indignation and amazement. I once feared I would faint upon staring at a jar of conjoined twins for too long, my mind not grasping the severity of what I was looking at. This museum holds some of the world’s most obscure medical anomalies, creating an atmosphere that appears almost supernatural. The museum’s method of displaying its specimens, however, have in recent times reflected poorly on their ethical considerations when dealing with human remains. For this reason the Postmortem Project was created in order to shed light on past insensitivities within the museum's foundation.

While created with the intention of addressing these ethical concerns, the Postmortem Project highlights the importance of education and transparency in showcasing human remains. This project hopes to engage in a dialogue about the history of the individuals who once lived in the bodies now plastered on the walls and in glass cases within the Mutter Museum, as well as share the history of medicine and diseases. The efforts and goals of the project will allow for deeper reflection upon the lives of those who ended up at the museum.

The Postmortem Project also tells the history of the exhibitions at the Mutter Museum, dating back to the late 1880s when nascent concepts like consent and ethics were just beginning to take form. However, in today’s climate where museums require certain documents to legitimize their ability to showcase certain exhibitions, the Mutter Museum is facing some trouble. People are questioning the Mutter Museum on where many of their remains came from, those that weren’t donated by the families or the victims themselves, and the answer is simple but also hard to hear. Most of the specimens showcased at the museum came from the anonymous poor, but before the 1950s, people were not donating bodies to museums or scientists. So, doctors and scientists resorted to the next best thing, which was grave robbing. It was either that or enlisting the aid of the Resurrection Men, an infamous group who murdered multiple people in the 1830s for the purpose of selling the bodies to medical schools for a profit. Thankfully, the Pennsylvania Anatomy Act of 1883 put an end to the practice of grave robbing and provided the legal necessities for physicians to receive cadavers for study. This, unfortunately, did not protect the resting spots of the poor, whose remains comprise a majority of the specimens in glass cases and jars and displays at the Mutter Museum.

A major component of the Mutter Museum’s origins come from one of Philadelphia’s oldest hospitals/mental asylums. Located in West Philadelphia, Blockley Almshouse featured a hospital, housing for the poor, a workhouse, and also a mental asylum. Prior to laws regarding cadavers, Blockley partnered with Mutter, offering them specimens they had no room for, most often without patient consent. It is said these specimens were Philadelphia’s poor, who, when they died, had no one to claim their body or money for a respected burial. Another problem facing the moral dilemma of the Mutter Museum is race and how it has affected the care and treatment of patients and their bodies postmortem. Of course, race does not prevail in death – a skull remains a skull – but knowing the story or the history of that human skull nailed to the wall of a museum can surely change the perspective and thoughts that come to mind when gazing upon Josef Hyrtl’s collection.

Museums all over the world have been facing mass criticism for the lack of ethics and thought behind the artifacts and specimens on display. The British Museum is most notorious, for many of their artifacts are stolen relics from all over Africa. While museums showcase amazing facets of human society that allow us a glimpse into the past, there are legal and ethical concerns raging that question the validity of boasting stolen artifacts, and people, in the case of the Mutter Museum.

Consent is a word that has been circulating throughout the media for the last few years, granting bodily autonomy to millions of people who previously would not have believed they were entitled to it themselves. But what about postmortem consent? The consent of the deceased (or lack thereof) is the question that is causing the Mutter Museum to rethink their exhibitions and look to the public for guidance. The Mutter Museum is not for everyone, but for those medically inquisitive like myself, it is a place where people’s worst health scares are brought to light in a way that makes even the most unfortunate death significant. The skeletal remains can be seen as symbols that reflect a wide range of human experience, and ultimately raise questions about prenatal care and genetics, and, as the Postmortem Project entails, consent.