OWHC Travels: Safety, Delight, and Modern Comfort in Historic Urbanity

With the rush of adrenaline pushing my late-night race into Queens, my take-off from JFK Airport was a surge of thrills, fears and unknowns launching me, alone, into whatever awaited me on the other side of the Atlantic. My name is Aidan DeLuca: I’m a recent graduate of architecture from Jefferson University, a practicing designer with CRB Group, Inc, and an aspiring civil servant. This night of excitement-overload was August 28th, 2024, and the start of my quite unforeseen venture to Europe. I had received word of the Organization of World Heritage Cities (OWHC) and their generous young-traveler’s scholarship at the end of June, and without much expectation decided to apply simply for the fun of it. Out of my options, I chose to spend a week in Brussels, Belgium, another in Berlin, Germany, and then ultimatelyreturn to my home in Philadelphia for a continued week of comparative study. The focus of my application was very specific to my professional interests, saying that my studies in Europe would evaluate public safety, walkability, and transit along with the reflection of each city’s history in the current states of these places. Historic preservation isn’t my specialty, but respecting the integrity of the city’s history while finding solutions to issues of livability is a strong driver for my career in Philadelphia.

Two weeks went by, and I continued my typical, daily efforts of working and studying for my professional exams, quickly forgetting this scholarship. Then of course, I received the good news, and my trajectory spun to a sudden burst of travel-prep as I really realized I was about to travel abroad alone for the first time in my life. Looking back, I think I shoved that thought as deeply into the back of my mind as possible just to avoid the anxiety. I’m clearly one to take on uncomfortable circumstances for the sake of the thrill, but this was also only my second time outside the U.S. and third time away from the East Coast. Enough said, it was stressful. Nevertheless, I’m extremely passionate about bettering my awareness and knowledge as an architect and future civic designer, so the strongest voice in my head said, “Do this."

The things I particularly looked forward towards were the Northern European specialties on urban living and efficient transport. Concepts of ecological cleanliness and ergonomic design are components of an overall respect for good living that I hypothesized to be more successful in these places. My research on achieving wholesome city-life has often presented me with cities like Berlin as a case study; therefore, I was optimistic to learn to improve the city of Philadelphia from this travel.

Brussels, Belgium

Looking back at the decision to explore Brussels, I find it humorous: the choice was purely out of convenience (its proximity to Berlin), and this trip absolutely put the city on the map for me (and the country of Belgium for that matter). I didn’t know anything about the place, and patted myself sarcastically on the back once I discovered it was French-speaking (a language of which I know zero). I shamefully followed the American trope, the classic deer-in-the-headlights approach, to traveling here. Somehow I survived, and my English, Italian and Spanish found me companionship in my hostel.

I’m now finding that my first impression of the city is in-line with many other visitors’: there is a viscous cosmopolitan atmosphere. For a Dutch-speaking state, the city is remarkably anti-Dutch-speaking. The heterogeneity felt welcoming, and I think this helped me flow more easily into the Brusselonian stream. One of my new friends Sebastian, an American student in Leuven, Belgium, was extremely passionate on the topics of Belgian politics and civil rights. Upon hearing my travelling mission as a designer, he toured me through the metropolitan area for the week I was there. He gave me valuable insight and showed me scenes in neighborhoods of how the city handles itself, from its pretty face to its low-end communities. Seeing the “bad side of town” is a crucial component of my studies: I need to audit exactly how a city provides for its lower-income and often marginalized communities.

I determined (within the limited scope of my analysis) that Brussels is good to its occupants. Public transit is efficient, cheap, and plentiful. Although there is constantly much unfinished development in the city’s architecture and infrastructure, it still felt very high functioning. I was never slowed in my travels, nor was I ever stranded. The atmosphere felt safe at as whole. I found very few spaces in public areas that disturbed me. To name a few examples, I’m referring to frequent highway underpasses that hide assailants, lengthy underground walkways, and accumulations of factory buildings in residential areas (all of which are unfortunately quite common in Philadelphia). I found a preserved, good quality of life even within the lower income communities, and yet there were simultaneously many features that reminded me of Philadelphia. The communities felt authentic to their individual identities. There was clear reference to the countries of origin and a celebration of the cultures, but there was not an apparent divide or segregation between the communities either. I learned of the quasi-colonial relation between Belgium and Congo for example (Congo was technically not a colony, rather the private estate of the King of Belgium). Consequently, Congolese today make up a large community in the city.

There is also a slight roughness to the city, but one that does not outshine the beauty of its rhythmic streets and unique, architectural conditions. On my first day, I recall taking a glass elevator to climb the hill to the Palace of Justice and having the vantage to view what I later referred as a “patchwork quilt." I loved every moment of Brussels.

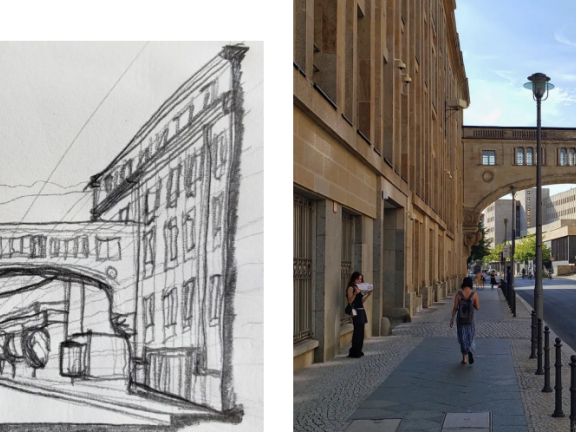

Berlin, Germany

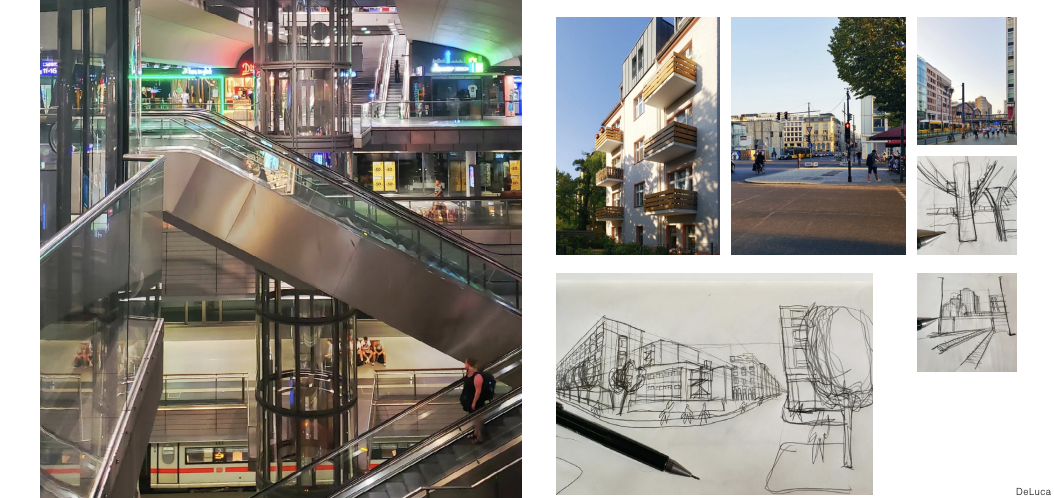

As I took the early morning Deutchbahn to Berlin, I realized I was sad to leave Brussels. The city that had never existed on my radar was now among one of my favorite places. Berlin after all was the city of my original excitement (I had even invested in 2 months of preparatory German to optimize the academic of my experience). On this train, I prepared myself for yet another intense cultural immersion, but I was still left surprised by the inconvenience of the journey to my hostel booking. I was culpable in part for this circumstance, as my booking was in the Southwest periphery of Berlin beside Osdorfer Straße station (both for the cheapness and for the academic quality of being present in a peripheral neighborhood). It took some time and navigational gymnastics to find my way to rest, but it gave me a chance to familiarize myself with the Berliner infrastructure. My first impression lasted: Berlin is not as navigable as I had hypothesized. In fact, my coming days revealed the unexpected parallels between Berlin and the ideal of the American suburb.

This was the most comedic reality I could-have imagined: I recall the vague feeling that this was the ideal sprawl of New Jersey. Everything resonated with the American suburban notions: enter the city for white collar work; leave the city for white collar living; drive your car; never walk; material is made to be purchased, not to last; expand, sprawl, expand. I audibly laughed when I found my first T.K. Maxx, an apparently German variant of the retail liquidation chain T.J. Maxx. It felt like the model state of America, but not the model state that I wished for America. I found that I needed to be Berlin-savvy to really exist contently in the city; I needed to preemptively own a vehicle, know where to go for resources, and most importantly fit into its culture to feel at home.

Back Home in Philly

Near the end of my week in Berlin, I was already exhausted. I loved the sensation of these adventures, but the commitment of achieving explorative, academic excellence while traveling entirely alone had worn me down much quicker than I had expected. I was quite content to be returning to Philadelphia, and on my way back I began to consolidate my studies and observations into a cohesive summary that would serve to guide me in my formal analysis of the City of Brotherly Love.

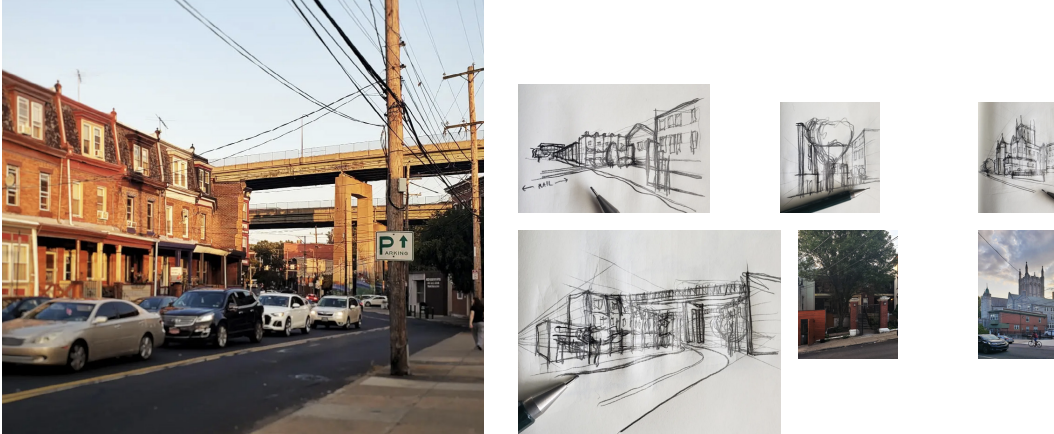

Living here in Philly as a transit commuter without a car, my lifestyle in each was as similar as it could be, so I could more easily compare my travels between the three cities. I suppose much of my headaches here arise from commuter troubles, but I tried to take an unbiased look at the aspects in which Philadelphia succeeds and where it can pull strategies from Brussels and Berlin. Looking at the transit efficiency, it is difficult to compare. Philadelphia does not have transport that occurs in a timely fashion. Buses are often infrequent, and the ones that are frequent will consistently have long delays and often cancel. This happens less with trains, but “less” is the key word. However, I’ve adapted my lifestyle to accommodate these uncertainties. On the other hand, the metros and rails I used in Brussels and Berlin acquainted me with a luxurious reliability in transit (although I was reminded not to take it for granted when I returned). Driving in these cities was still very popular, but I couldn’t fathom why someone would opt to drive with such affordable and reliable modes of movement already at their disposal.

The safety of the stations was another feature to which I was purposely attentive. I pay close mind to the thought of safety that is put into station construction: in Philadelphia, I experience many situations of tunnel underpasses with tight turns around corners which put the users in extremely vulnerable positions; such examples are Suburban Station and North Philadelphia Amtrak Station. Traveling through the metros alone can be unsafe too, such as Broad and Market Street Station which feature many fishbowl moments where a user has difficulty observing their surroundings while others can easily peer at the user. In Brussels and Berlin, I observed a consistent openness of transit stations where all surroundings were in view and users were kept away from vulnerable spaces. There was a direct flow of foot-traffic rather than Philly’s common weaving in-and-out of nonsensical corridors.

Walkability is important too. A resident needs access to pleasant and convenient foot-travel in the city, and searching for amenities on the fly in two entirely new cities is a sure way to gauge where they land on this metric.Brussels is a small city; in addition, I was staying downtown, so finding everything I needed (in multiple options nonetheless) within a twenty-minute walk (or even quicker with transit) was achievable. Berlin was the opposite: being very cartesian in design, everything felt extremely out of scale for a pedestrian. Roads were typically multilane, buildings were tall and wide, and I often found myself walking thirty to forty-minutes to the next amenity (even as simple as a grocery store or café). Philadelphia falls in between. This city has a better respect for the walking life than Berlin, but the integrated zoning of necessary-commercial and residential (as opposed to luxury-commercial like expensive restaurants and clothing chains) should be adopted from a city like Brussels and employed in Philly. Being able to walk from home and obtain groceries, medicine, and other important resourcesin a timely fashion is a concept for which I highly advocate.One Philadelphian neighborhood I used in my study was East Falls, an exquisitely constructed residential area which hosts some useful local amenities (a library, barbershops, corner stores, a pharmacy, etc.), all of which are spread evenly and equitably through the area. Conversely, I took a walk through Germantown where the amenities are consolidated to an axis road, Chelton Avenue, that can be a lengthy trek for those dwelling in theouter edges of the neighborhood.

Of course, this trip couldn’t remain purely in the realm of contemporary city-use. I needed to consider how these elements of livability complimented and contrasted the vibrant histories. To me, Philadelphia feels like a series of time capsules, showcasing different eras of North American vernacular. Walking around in Germantown or Chestnut Hill often becomes a homework-trip, and I am frozen in awe around each corner when I spot a hidden treasure of a different architectural style. Berlin gave me the same experience whenever I ventured into the periphery. The residential suburban areas were beautifully lined with uniquely built but modest housing. I adore German construction technology, and I find every detail so beautiful from the window hingers to the fence posts. It’s good to see an apparent system where the restoration of these building-parts is accessible. Many areas of Philly too have amazing buildings, even if they are the seemingly (but not quite) repetitive rowhomes, and I think many Philadelphians would agree how sad it is to witness their deterioration. However, Berlin’s history in terms of architecture is at large much more modernist. These constructions are more recent than much of Philadelphia, so systems like roads, highways, and trains are organized more neatly. Brussel’s streets share more similarity with Philly in its occasionally disorderly intersections and never-ending construction projects. Strangely this made them both feel livelier to me. As a designer, I suppose I find my element in the chaos of a constantly evolving city rather than one that feels complete (and therefore stagnant).

The Power of Travel

There is much for me to absorb from these cities for the sake of my career, and there is much more still to be obtained by further visits and longer stays. My greatest take-away was the importance of respecting the occupants’ delight in a city. I feel that Philadelphia can often succumb to the forces of utilitarianism or hyper-capitalism, and I’ve now been reminded how crucial it is to achieve cheap, accessible resources and pastimes for all. Frequent, free, non-exclusive events is a wonderful thing that I experienced abroad, and the utter comfortability was so refreshing. This trip gave me a taste of two regions and cities to which I had no prior mental-image, so naturally I’d like to return with more involvement in my professional studies. With the perspective I have now, I feel much more equipped to pursue new ideas in city planning, but I have also learned new strategies in quickly auditing a city foreign to myself. Whether I decide to return to these places in the near future or spread my net to other parts of the world, I will continue to carry the thoughts of these three weeks as examples that will propel me even further into my architectural passions.

Read the full OWHC report from Aidan's Trip!

This article is part of GPA's Young Professional Travel Series.