A Global Conversation with John F. Smith III

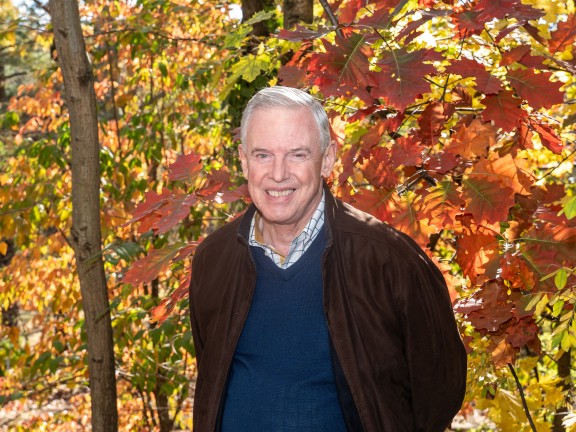

It’s not every day that we get to speak with someone whose leadership journey spans from the decks of Navy ships to the boardrooms of civic and global organizations. John F. Smith III, founder of the Global Philadelphia Association, civic entrepreneur, and former attorney, has dedicated his life to service, collaboration, and inspiring transformative change. His involvement in founding and shaping the Global Philadelphia Association played a pivotal role in establishing and advancing Philadelphia’s standing as a World Heritage City, fostering a global mindset throughout the region, and uniting diverse organizations to showcase the city’s rich history and promising future.

As the 2024 Lifetime Achievement Awardee at the 10th Annual Globy Awards, John’s leadership legacy is being celebrated in a milestone year for the organization he founded. From his early days leading river patrols in Vietnam, where he honed his ability to lead through diverse experiences and vision, to his efforts as a prominent Philadelphia attorney working with organizations in the public eye, John’s career exemplifies what it means to lead with purpose and tenacity.

This conversation provides an opportunity to reflect on his remarkable journey, the values that have guided him, and the incredible impact he has had on Philadelphia and beyond. Through his steadfast commitment to civic engagement, John F. Smith III has helped shape not only the city’s past but its future as a truly global hub.

A bold vision, when paired with unwavering determination, can transform not just a career, but an entire city’s place in the world.

Your time in Vietnam and later as a lawyer in Philadelphia exposed you to diverse communities and challenges. How did these experiences influence your leadership style and approach to civic engagement?

I went to Officer Candidate School in the fall of 1963 to join the Navy. Together with a large number of people that I had never known before, we were given about 150 days of instruction, after which we were thought to be worthy of being commissioned as officers in the U.S. Navy. The Navy experience was terrific for me, not only because of the experiences I had but also because of the incredible variety of people that I met and came to know—people from all over the country, from every race and background, and every economic level. It was really a good representation of the United States.

That was a terrific grounding for me to pursue my ambitions in the years after, including the founding of Global Philadelphia. One of the early experiences I had in the Navy was learning how to relate to people. Because of the great variety of people, I had many different ways of testing what I thought was best.

That experience helped me greatly. When I first served on a destroyer off the northern coast of Cuba, I was exposed to a global situation. It was the immediate aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis, and we were recording the voices of Cubans and Russians still in Cuba at the time.

Later, when I volunteered to take an assignment in Vietnam, I became the operations officer of a river division in the Mekong Delta in the southern part of the country. In that capacity, I was given command responsibility to lead a group of sailors.

You quickly figure out what works and what doesn’t. This wasn’t about telling people what to do; you had to understand them and motivate them to want to do what the mission required. The Navy was fond of this saying: it's not leadership over people, it's leadership through people. That's a fundamental difference, I think, from the way many people try to lead, and usually unsuccessfully.

I learned, sometimes the hard way, that the best way to relate to people is first to listen to them, make sure I understand where they were coming from, and then gather them around a vision that the Navy and I both felt was important. That whole process of gathering people around a vision was hugely important in everything I did, including helping to form the Global Philadelphia Association.

As a young lawyer, what pivotal experiences during your early career shaped your vision for promoting a global perspective in Philadelphia?

The law firm I joined was called Dilworth Paxson. Dilworth was very engaged in representing public as well as private clients. Some of my earliest experiences were representing the Philadelphia Inquirer and SEPTA, both of which are very much in the public eye.

I gradually came to understand that, to be their lawyer, I needed to do more than just understand what the cases had to say and more than just write a halfway decent brief. I had to understand the organizations themselves, and probably most importantly, understand that they were in the business of serving the public. Unless I knew that was their large and important mission, I wouldn’t have been able to capture what they wanted in their legal positions. That was extremely helpful.

Later on, I learned quickly that you need to figure out how to communicate as clearly as possible. You don’t have much time, especially when you’re trying to make an argument in front of a judge. A judge sitting up on the bench in a black robe has many other things to do besides listen to you. So you better say what you have to say truthfully and forcefully, and hope you don’t outwear their patience. I learned very quickly that you can't just go on forever. You better answer the question.

When you were involved in the efforts of trying to win Philadelphia the World Heritage City status, how did those skills play into pushing for the designation?

Global Philadelphia itself was founded in 2010. It’s been around for almost 15 years now, and the World Heritage City designation was acquired in 2015. To get that designation, we first had to figure out what it was.

In 2011, after Global Philadelphia had begun, I still didn’t know what a World Heritage City was. I had the opportunity to go to the Penn Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology one day and meet the director of the museum. He knew that I was involved in founding Global Philadelphia, and he asked me a very pertinent question: "Why isn’t Philadelphia a World Heritage City?" I had no idea what he was talking about.

He said, "You may not know now, but you should figure it out. It could be very important for Philadelphia." He introduced me to Professor David Brownlee, a distinguished member of the Penn faculty, and I said, "David can tell you what a World Heritage City is all about." From the very early stages, Dr. Brownlee and I became good friends and closely involved in trying to determine whether it was worthwhile. We quickly concluded that it was.

To be admitted as a World Heritage City, you have to get approval from all the other cities in the Organization of World Heritage Cities or OWHC. Our executive director, Zabeth Teelucksingh, and I, as board chair, knew that Philadelphia had a great case to make. Philadelphia’s mayor, Michael Nutter, became a strong supporter. Nevertheless, in order to persuade the OWHC to admit Philadelphia, we went through a lot of effort. Some of it involved researching Philadelphia’s historical strengths and virtues. Part of it involved visiting other cities that had the status already. We did a tremendous amount of travel. I went to places like Oaxaca, Mexico, and Florence, Italy. We traveled to make the acquaintance of these other cities and establish our credibility, persuading them that Philadelphia was worth allowing into the organization.

As you know, Jessica, at the time there was no U.S. city with the World Heritage City designation. We worked at it for about three years before we had the opportunity to go to Arequipa, Peru with Alan Greenberger, the deputy mayor at the time, and Sylvie Gallier Howard from the city’s Commerce Department, to present Philadelphia’s case. In order for Philadelphia to succeed, a key OWHC bylaw had to be changed. After a fairly tense moment, a vote was taken, the bylaw was changed, and Philadelphia was accepted as a member. We were thrilled.

Throughout all these trips, did you feel more confident about the designation for Philadelphia, or did exposure to these other cities highlight things Philadelphia could improve on that you wanted to integrate into GPA?

We went into it with a very optimistic frame of mind. We knew we had a remarkable city to sell. The biggest challenge was that the World Heritage site in Philadelphia was small—basically just the city block that includes Independence Hall. Most of the other cities in the organization have extensive territories. For example, in Paris, the World Heritage site extends along the banks of the River Seine for about a kilometer on either side.

We were concerned that Philadelphia’s "postage stamp" site might not be enough. But, of course, it turned out that it was. We were aware and proud of the fact that more history took place in that single block of Philadelphia than in many other places around the world.

Did you want to add anything about the gap you saw in Philadelphia that motivated you to pursue World Heritage City status and the creation of Global Philadelphia?

Going back to the beginning of Global Philadelphia, in 2009, I was the board chair of International House Philadelphia. I knew the heads of most of the other international organizations in the city, like the World Affairs Council, the International Visitors Council, the World Trade Center of Philadelphia, the Nationalities Service Center, and the Welcoming Center for New Pennsylvanians. It became clear that, despite the accomplishments of all these wonderful organizations, they were not fully appreciated on a city-wide scale for the work they did.

Philadelphians didn’t have an international mindset. That surprised me because, going almost all the way back to the founding of the city, we were the most prominent English-speaking city in the Western Hemisphere. Later, in the 1800s and early 1900s, Philadelphia was arguably the most important industrial city in the world. We were a world center of manufacturing right through World War Two. Yet, by the latter part of the 20th century, after World War II, Philadelphia had started to think of itself just as a local city—a good city, an important city, but not a world-renowned city.

In the early 2000s, there was an effort to host the International Olympic Games in Philadelphia. A consortium was formed to make the case and prepare an application. The U.S. Olympic Committee came back to the organizers and said, "Sorry, but a poll was taken internationally, and not enough people know about Philadelphia on a global scale. We don’t think your candidacy will go very far. Please withdraw your application."

That really upset me. We decided that if Philadelphia wasn’t well known globally, we needed to do something about it. This led to a series of conversations with the leaders of the other organizations, and after a year of breakfast and lunch meetings, the idea emerged to create Global Philadelphia.

As GPA celebrates its 15th anniversary, how have you personally seen the organization evolve, and what achievements are you most proud of from its first decade?

Back in its early days, GPA was an all-volunteer organization. That changed with the hiring of Zabeth Teelucksingh as our executive director. We found a home at Reed Smith, my law firm at the time. GPA was housed in some of the firm’s unused offices. Gradually, our resources grew. In time, Brandywine Real Estate Investment Trust took an interest in us and gave us favorable terms on a lease at 2 Logan Square. That’s where the Association is headquartered today.

GPA has certainly grown, with over 200 members now, which is a significant change from where we started. In terms of impact, one of the biggest transformations has been Philadelphia’s increasing recognition as a global city. I’m incredibly proud of the role we’ve played in that shift. For many years, the city may have lacked that international visibility, but through our efforts and support for our members, we’ve helped bring it back.

I’m particularly proud of some of the initiatives we launched, such as the global expositions we ran for about seven years, an Emerging International Journalism Program, and an interactive website. These were and remain important in showcasing Philadelphia on the world stage. We also created a website and maintained a calendar listing what our members were doing and promoting international activities happening in the city. All this helped raise awareness and expand the city’s global consciousness.

Additionally, we recognized early on that engaging with political leaders was crucial. So, we began hosting meet-and-greets with candidates for mayor, city council, and other political offices, providing a platform for them to listen to our vision for Philadelphia as a global city. This initiative helped stir the conversation and build momentum.

The opportunity to secure Philadelphia’s status as a World Heritage City was a game-changer. It was a pivotal moment that really pushed our efforts forward. I must give credit to Mayor Michael Nutter and his deputy, Alan Greenberger, who supported the idea from the start. With their backing, Philadelphia began to make real strides on the international stage, and I’m proud of how far we’ve come in that regard.

What is it specifically about Philadelphia that inspires your long-term commitment to its growth and global recognition?

When my wife, Susan, and I first moved to Philadelphia, we settled in Society Hill, which is the colonial part of town. We had a tiny row house that was only 13 feet wide, but it had a significant feature—steps leading up to the front door, a "doorstoop," which was common in the neighborhood. People spent time on their steps, engaging with one another, and this created a real sense of community.

A couple of years later, I was encouraged to run for president of the Society Hill Civic Association, and I had the honor of leading it during the bicentennial year in 1976. It was a time when the pride of the city was clearly on the rise. I learned that with some effort and imagination, you could inspire people to get behind a cause. If you could excite people and thank them for their involvement, you could accomplish almost anything. These early experiences in Society Hill, and later in Villanova, helped shape my belief that people coming together can bring positive change. I was happy to be part of that momentum.

It’s clear that family plays a key role in your life and career. Why do you feel having a strong support system is crucial for success?

It almost goes without saying, but I couldn’t have done any of this without a supportive partner. My wife, Susan, has been there every step of the way, tolerating the time I spent on various endeavors and being a true partner. She attended countless events, including many "rubber chicken dinners," with charm and enthusiasm. She was truly integral to everything I’ve achieved, and I’m deeply grateful for her support.

What leadership strategies did you find most effective in uniting such a diverse coalition of organizations for Global Philadelphia?

When we started Global Philadelphia, we faced the challenge of uniting different organizations, each with its own mission, funding sources, and space in the civic arena. These organizations were initially hesitant to join forces, fearing they might lose funding, board members, or visibility. We had to be very sensitive to the concerns and needs of each organization and make sure they felt that their contributions were valued.

The success of Global Philadelphia has been driven by the fact that we always prioritized the interests of our members. We made sure that the association was not just focused on its own prominence, but also on supporting the individual organizations that helped form it. By paying attention to their needs and serving them, we kept the coalition united and moving forward.

What are the greatest opportunities and challenges you foresee for Philadelphia in maintaining its status as a global city and a World Heritage City?

There are always tremendous opportunities for Philadelphia, and it’s critical that we keep imagining new ways to present the city as a global hub. We can’t rest on our laurels. However, one of the challenges is ensuring the city itself remains fully engaged in this global vision.

Sometimes, there’s a tendency to think that Global Philadelphia can handle the international side, and the city can focus on its local issues. But the global effort can’t succeed unless the city’s public bodies—particularly the mayor and city council—get behind it. Thankfully, we’ve made progress in this area. City Council has been great, and I’m hopeful that the new mayor, too, will prioritize this global dimension. I believe this global focus will only benefit her administration and Philadelphia as a whole.

As a Distinguished Lifetime Achievement Awardee, what advice would you give to emerging leaders aiming to make a lasting impact?

First, remember—it’s not about you, stupid! Leadership is about understanding others, their goals, and finding ways to connect your vision with theirs.

Second, when you take on a project, you have to work harder than everyone else. You have to be seen as the hardest worker in the room, because that’s the only way to earn respect and empower others to work with you.

Third, be respectful but fearless. While you may have doubts along the way, pursue your course with confidence. You’ll face criticism and opposition, but if you believe you’re right, keep pushing forward. And if you realize you’re wrong, be quick to adjust.

Fourth and last, remember that the two most powerful words in the English language are "imagine" and "thank you." You need to inspire others through your imagination, and you must express gratitude to those who help you. "Thank you" is never overused—it’s essential to acknowledge others’ contributions at every turn.