A Global Conversation with Jillian Pirtle: Exploring the Life of the "Great Lady" From Philadelphia, Marian Anderson

Jillian Patricia Pirtle is a celebrated stage and opera artist with a deep passion for the arts. As a trained vocalist, actress, and historian, she has dedicated her career to both performing and preserving history. Her love for music and storytelling has fueled her mission to educate and inspire others through the rich narratives of legendary figures in the arts. In addition to her extensive background in musical theater and opera, she is the CEO of the National Marian Anderson Museum & Historical Society, where she works tirelessly to uphold the legacy of the legendary contralto and humanitarian.

Marian Anderson’s name resonates not only in the world of classical music but also in the broader cultural and historical landscape. She shattered racial barriers, overcame adversity, and used her voice—both literally and figuratively—to advocate for equality and justice. Today, her contributions continue to inspire artists and activists alike. In this conversation, Jillian shares her insights on Marian Anderson’s significance, the history of the museum, and ongoing efforts to preserve Anderson’s legacy for future generations.

This article was originally published in 2021, and is being republished in honor of the historic reopening of The National Marian Anderson Museum & Historical Society following a devastating flood that occurred five years. All events related to the reopening of the museum can be found at the end of the article.

For those who may not know, could you tell me a little about Marian Anderson?

Our great Marian Anderson was born on February 27th 1897. Marian Anderson was the oldest of three daughters born to John and Anna Anderson. John was a loader at the Reading Terminal Market, while Anna had been a teacher in Virginia. In 1912, John suffered a head wound at work and died soon after. Anna and her three daughters moved in with John’s parents, while Anna found work cleaning, laundering and scrubbing floors. Marian attended William Penn High School (focusing on a commercial education course to get a job) until her music vocation arose. She transferred to South Philadelphia High School, focusing on music and singing frequently at assemblies, and graduating at age 18.

She applied for admission to a local music school, but was coldly rejected because of her color. Marian’s musical career began quite early, at the local Baptist church in which her father was very active. She joined the junior choir at age six. Before long, she was nicknamed “The Baby Contralto.” When she was eight, her father bought a piano from his brother, but they could not afford any lessons so Marian taught herself. When Marian was 13 years old, she joined the senior choir at church and began visiting other churches; becoming well-known and accepting invitations to sing. She became so popular, she would sometimes perform at three different places in a single night.

Finally she summoned the confidence to request five dollars per performance. In 1919, at the age of 22, she sang at the National Baptist Convention. When she was 15 years old, Marian began voice lessons with Mary Saunders Patterson, a prominent black soprano. Shortly thereafter, the Philadelphia Choral Society held a benefit concert, providing $500 for her to study for two years with leading contralto Agnes Reifsnyder. After she graduated from high school, her principal enabled her to meet Guiseppe Boghetti, a much sought-after teacher. When he heard Marian audition, singing “Deep River,” he was moved to tears. Marian’s initial invitations to sing grew to actual tours, focusing on black colleges and churches in the South. William “Billy” King accompanied her and also served as her manager. Soon she was making $100 per concert.

On April 23, 1924, they took a giant step and held a concert at New York’s Town Hall. Unfortunately, it was poorly attended and critics found her voice lacking. Marian was so discouraged, she contemplated abandoning her career choice. But shortly after, she won a singing contest through the Philadelphia Philharmonic Society and then, in 1925, she entered the Lewisohn Stadium competition. She beat 300 rivals and sang in New York’s amphitheater with the Philharmonic Orchestra accompanying her. This concert was a triumph and gained her the attention of Arthur Judson, an important impresario, who put her under contract. In 1926, Marian toured the eastern and southern states, adding songs to her repertoire.

On December 30, 1928, she performed a solo recital at Carnegie Hall. A New York Times critic wrote, “A true mezzo-soprano, she encompassed both ranges with full power, expressive feeling, dynamic contrast, and utmost delicacy.” But despite this success, her engagements were stagnating; she was still performing mainly for black audiences. Marian then obtained a scholarship through the National Association of Negro Musicians to study in Britain. On September 16, 1930, she performed at London’s Wigmore Hall. She returned to the U.S. only to return to Europe again, on a scholarship from the Julius Rosenwald Fund. She was intent on perfecting her language skills (as most operas were written in Italian and German) and learning the art of lieder singing. At a debut concert in Berlin, she attracted the attention of Rule Rasmussen and Helmer Enwall, managers who arranged a tour of Scandinavia. Enwall continued as her manager for other tours around Europe.

Marian returned to the U.S. for more concerts and then, in 1933, returned to Europe again through the Rosenwald Fund. From September 1933 through April 1934, she performed at 142 concerts in Scandinavia alone, even singing before King Gustav in Stockholm and King Christian in Copenhagen. She received a rare invitation to sing from Jean Sibelius, a 70-year-old famous Finnish composer. He was so moved, he dedicated his song “Solitude” to her, saying, “The roof of my house is too low for your voice.” She followed those concerts with appearances throughout Europe. This tour concluded in 1935 with an international festival in Salzburg called the Mozarteum. Arturo Toscanini, a very prestigious conductor, heard her sing and told her, “Yours is a voice such as one hears once in a hundred years.”

Another famous impresario, Sol Hurok, also heard her sing shortly after that and drafted a contract with her for American concerts. On December 20, 1935, Marian appeared for the second time at New York’s Town Hall. This time she was a great success. She also gave two concerts at Carnegie Hall, then toured the states from coast to coast. She went on to tour Europe again, and even Latin America, through 1938 – performing about 70 times a year.

Can you discuss some other significant moments in her life?

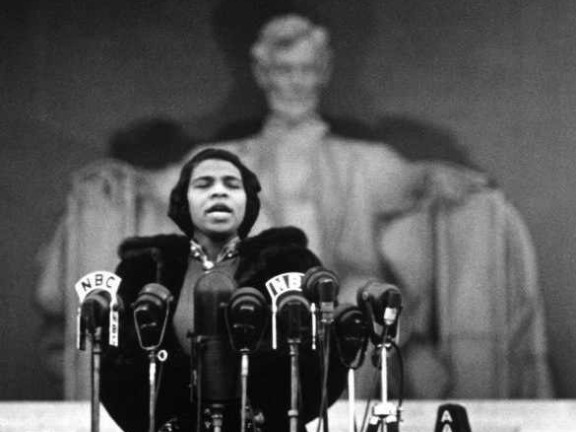

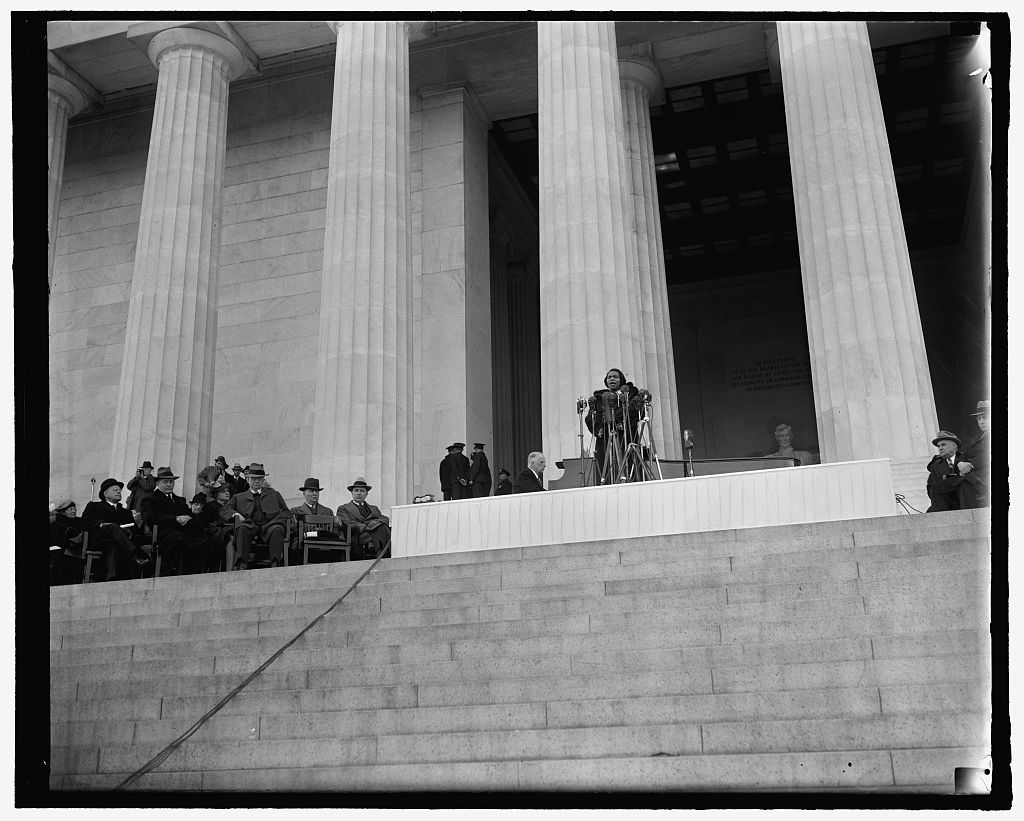

Throughout her life, Marian had experienced racism, but the most famous event occurred in 1939. Hurok tried to rent Washington, D.C.’s Constitutional Hall, the city’s foremost center, but was told no dates were available. Washington was segregated and even the hall had segregated seating. In 1935, the hall instated a new clause: “concert by white artists only.” Hurok would have walked away with the response he’d received, but a rival manager asked about renting the hall for the same dates and was told they were open. The hall’s director told Hurok the truth, even yelling before slamming down the phone, “No Negro will ever appear in this hall while I am manager.” The public was outraged, famous musicians protested, and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt resigned from the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), who owned the hall. Roosevelt, along with Hurok and Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), encouraged Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes to arrange a free open-air concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial for Easter Sunday. On April 9, Marian sang before 75,000 people and millions of radio listeners.

About her trepidation before the event, she said, “I said yes, but the yes did not come easily or quickly. I don’t like a lot of shows, and one could not tell in advance what direction the affair would take. I studied my conscience. As I thought further, I could see that my significance as an individual was small in this affair. I had become, whether I like it or not, a symbol, representing my people."

Several weeks later, Marian gave a private concert at the White House, where President Franklin D. Roosevelt was entertaining King George VI and Queen Elizabeth of Britain. In 1943, Marian performed at Constitution Hall, at a benefit for Chinese relief. She insisted the DAR suspend its segregated seating policy for the concert. Later, she said, “I felt no different than I had in other halls. There was no sense of triumph. I felt that it was a beautiful concert hall, and I was happy to sing in it.”

In July 1943, Marian married Orpheus H. Fisher, a Delaware architect she had known since childhood. They lived on her “Marianna Farm” in Connecticut. During World War II and the Korean War, Marian entertained troops in hospitals and bases. By 1956, she had performed over a thousand times. In January 1955, Marian debuted at the New York Metropolitan Opera as Ulricia in Guiseppe Verdi’s “Un Ballo in Machera” (The Masked Ball) – the first black singer as a regular company member. She was 58 years old and, feeling past her vocal prime, felt she overdid it out of nervousness.

In 1957, she toured India and the Far East as a goodwill ambassador through the U.S. State Department and the American National Theater and Academy. She traveled 35,000 miles in 12 weeks, giving 24 concerts. After that, President Dwight Eisenhower appointed her as a delegate to the United Nations Human Rights Committee. She sang at his inauguration, as well as John F. Kennedy’s in 1961. In 1962, she toured Australia. In 1963, she sang at the March on Washington for Job and Freedom. On April 19, 1965, Easter Sunday, Marian gave her final concert at Carnegie Hall, following a year-long farewell tour.

What are some other challenges and triumphs she faced?

During her career, she received many awards, including the Springarn Medal in 1939, given annually to a black American who “shall have made the highest achievement during the preceding year or years in any honorable field of endeavor.” In 1941, she received the Bok award, given annually to an outstanding Philadelphia citizen. She used the $10,000 prize money to found the Marian Anderson Scholarships. In 1963, President Lyndon Johnson awarded her the American Medal of Freedom. In 1977, Congress awarded her a gold medal for what was thought to be her 75th birthday. In 1980, the U.S. Treasury Department coined a half-ounce gold commemorative medal with her likeness. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan presented her with the National Medal of Arts.

She was confronted by racism everywhere she went, even if she tried to avoid such confrontations and hostile situations. In Europe, she was welcomed into the finest hotels and restaurants, but in the U.S., she was shifted to third- or fourth-class accommodations. In the South, she often stayed with friends. Simple tasks such as arranging for laundry, taking a train, or eating at a restaurant were often difficult. She would take meals in her room and traveled in drawing rooms on night trains.

She said, “If I were inclined to be combative, I suppose I might insist on making an issue of these things. But that is not my nature, and I always bear in mind that my mission is to leave behind me the kind of impression that will make it easier for those who follow.”

Early on, she insisted on “vertical” seating in segregated cities; meaning black audience members would be allotted seats in all parts of the auditorium. Many times, it was the first time blacks would sit in the orchestra section. By 1950, she would refuse to sing where the audience was segregated. In 1986, Orpheus passed away. In July 1992, Marian moved to Portland, Oregon, to live with her nephew (by her sister Ethel), conductor James DePriest. The following spring, she suffered a stroke and was restricted to a wheelchair. On April 8, 1993, Marian Anderson died of heart failure, at the age of 96. Over 2,000 admirers attended a memorial service at Carnegie Hall.

Why do you think she is important to Philadelphia?

Marian Anderson is an Artistic and Humanitarian world figure but she is endearingly known as the great Lady from Philadelphia. The humble beginnings, denials, hardships, hard work and triumph are the epitome of the Philadelphia Story. And despite the horrible things that Marian Anderson had to endure she decided to continue to make Philadelphia her home and the hub for her music and charitable efforts for the next generation of talented emerging artists. Philadelphia often fails to adequately acknowledge Marian Anderson and her legacy of the National Marian Anderson Historical Society & Museum as they should.

Could you tell me about some of the history behind the museum? I read that other performers like Duke Ellington performed there.

Ms. Anderson bought the house in 1924 and lived there most of her life, transforming the basement into an entertainment center. The area included a portable bar stocked with Anderson’s favorite drinks, champagne and water, a few pieces of furniture, and a piano. Here she would entertain friends and fellow musicians while resting up from world tours. Blacks during this time were denied access to most venues, so homeowners would enhance their basements to entertain friends such as Sir Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Count Bassie, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Paul Robeson, Lena Horne, Billie Holiday, Leonard Bernsteine, Maria Callas and more. Today, Ms. Anderson’s home / museum contains rare photos, books, memorabilia and films about her life.

The Marian Anderson Historical Residence Museum is the epicenter for the life and legacy of Marian Anderson. The understated exterior of the 19th century, three-story Marian Anderson House at 762 South Martin Street (also recognized as Marian Anderson Way between 19th, 20th and Fitzwater Streets in Center City) is listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places and bears a plaque from the Philadelphia Historical Commission. The Marian Anderson Residence Museum is also recognized on the National Register of Historic Places.

The organization was founded by Blanche Burton-Lyles and has existed for the past 23 years. Beyond the house itself, the surrounding area has since been named the Marian Anderson Village, which proudly hangs identifying flags throughout the neighborhood. In addition to the residence, the village contains Marian Anderson’s former church, elementary school, and a recreational center dedicated in her name.

In addition to promoting Anderson’s legacy locally, the society seeks to spread Anderson’s music throughout the world. The Scholars Program frequently supports young classical and opera singers from around the world. These artists perform regularly at events that the Society sponsors and helps promote their budding careers. The Society also partners with the Arts Empowerment Project to provide education, development and performance for all children in the arts in the tri-state area.

What are some of the items that you have on display at the museum? What are your favorites?

You can find in any given Thematic Exhibit that we have at the National Marian Anderson Museum on display. Marian Anderson’s performance gowns, photo albums, sheet music, letters, awards, recordings, family bibles and more. My favorite exhibit item which is permanent in the building is Marian Anderson’s treasured Steinway Piano.

Could you tell me about the fundraising efforts that you're working on for the Marian Anderson Museum and why it's needed?

The National Marian Anderson Museum and Historical Society was deeply affected by the tragic times our nation faces due to the COVID-19 health crisis. Like many other historical landmarks and museums, the National Marian Anderson Museum & Historical Society has been closed to the general public for in-person touring and live concert performances since early March. We have been unable to secure any government grants or financial assistance to support and sustain our operations. To make matters worse, the museum was damaged by a flood caused by aging pipes. The lower level of the museum suffered from 3 ½ feet of standing water and caused considerable damage to the museum’s artifacts, original hardwood flooring, the furnace and electrical systems, and more. A GoFundMe campaign has been established to help the Society pay for much needed repairs as well as sustaining programming and preservation for the 2020 season. Kindly visit the Go Fund Me campaign link or make a donation via our official secure website .

How have you been getting the word out about fundraising efforts?

We have tried in almost every way to make the local and national population aware of our plight and fundraising efforts through printed news publications, radio, television news broadcasts, social media, taking out ads and more.

For those who are interested, how can they donate?

For anyone interested in supporting and donating they can Kindly visit the Go Fund Me campaign link : Fundraiser for Jillian Patricia Pirtle by Nicole Koedyker : Support for Marian Anderson Historical Society (gofundme.com)

Or make a donation via our official secure website: Donate & Sponsor - National Marian Anderson Museum (weebly.com)